Do We Learn More Effectively From Print Than Screens?

This generation of students have grown up with all sorts of technology: from smartphones, tablets, to e-readers so they have been used to reading on screens their whole lives.

Image credit: weheartit.com

So it is reasonable to assume that their familiarity and preference for technology would translate into higher academic performance when using technology for learning and studying.

A new study has found that that is not the case.

The study, titled, Reading on Paper and Digitally: What the Past Decades of Empirical Research Reveal, shows that students learn more effectively from print textbooks than screens.

Authors Lauren M. Singer and Patricia A. Alexander, from the University of Maryland, summarized their findings in a Business Insider article.

They wrote, “while new forms of classroom technology like digital textbooks are more accessible and portable, it would be wrong to assume that students will automatically be better served by digital reading simply because they prefer it.”

Let’s take a more detailed look at the study, its implications; and also look at other reasons why reading on paper might be better for you than reading on a screen.

The Generation of Digital Natives

A YouTube video, which has gone viral, shows a one-year-old girl sweeping her fingers across an iPad screen and shuffling groups of icons. She is then handed a paper magazine which she then pinches and swipes as if it were a touch screen.

She pushes the magazine against her legs when nothing seems to happen just to confirm that her fingers still work.

The girl’s father taped the video as a naturalistic demonstration of a generational shift. In the video description, he writes, “technology codes our minds, changes our OS. Apple products have done this extensively. The video shows how magazines are now useless and impossible to understand, for digital natives.

It shows real life clip of a 1-year old, growing among touch screens and print. And how the latter becomes irrelevant. Medium is message. Humble tribute to Steve Jobs, by the most important person: a baby.”

So what was happening in that video?

His daughter may have expected the paper magazine to respond the same way that an iPad would.

Or perhaps she did not really have any expectations: she may have simply wanted to touch the magazine. Because babies naturally touch everything.

If you give a baby, who hasn’t used an iPad before, a paper magazine, they will swipe at it and even attempt to eat it. So perhaps the video shouldn’t make us think too much.

Especially since digital natives (the people who grew up in the age of digital technology) still use a mix of paper text and electronics; and they are familiar with both. And we should remember that familiarity with one doesn’t mean they don’t understand the other.

The video however does raise a few questions. How does technology change the way we read? How does reading on paper differ from reading on a screen?

Those questions apply not only to digital natives but anyone who goes from their office computer to their paper books or e-readers at home; anyone that embraces their kindle device but still prefers reading on paper; and anyone that doesn’t use paper books at all.

As digital texts deeper infiltrate the market, are we reading as thoroughly and thoughtfully as we used to? How do our brains process on-screen text in comparison to paper text?

Are our concerns about the effects of digital text paper-thin? Let’s refer to Singer and Alexander’s study.

The Study

Researchers in several fields (from psychology to computer engineering) have looked into answering the afore asked questions since the 1980s. The topic has been explored in over a hundred published studies.

Research before 1992 concluded that people read slower and less attentively on screens than on paper. Later studies confirmed that conclusion, but others, like Singer and Alexander’s study, have found some significant differences in reading speed and comprehension between paper and screens.

Image credit: Business Insider

Singer and Alexander conducted three studies to measure and compare the ability of college students to comprehend texts on paper and from screens.

Students were first asked to rate their medium of preference. They then read two passages: one online and one in print. After reading the passages, they were asked to describe the key ideas of the text, list the main points covered and to provide any relevant content they could remember.

When they finished, the researchers asked them to rate their reading comprehension performance.

The researchers found a great disparity between what students said they preferred (reading on screens) and their actual performance.

The main findings from the study were as follows (in the words of the authors of the study):

Students overwhelming preferred to read digitally.

Reading was significantly faster online than in print.

Students judged their comprehension as better online than in print.

Paradoxically, overall comprehension was better for print versus digital reading.

The medium didn’t matter for general questions (like understanding the main idea of the text).

When it came to specific questions, comprehension was significantly better when participants read printed texts.

The researchers further state that, “from our review of research done since 1992, we found that students were able to better comprehend information in print for texts that were more than a page in length. This appears to be related to the disruptive effect that scrolling has on comprehension.”

During exam time, students usually write their notes on paper and not digitally. Maybe they write down notes and carry it around because it is easier to transport paper than it is a laptop or tablet.

What they don’t really know is that reading notes from text is actually better than reading digitally. Professionals seem to understand that better as most of them prefer to take notes by hand and read on paper than on a computer.

Based on their findings, Singer and Alexander have a few thoughts and suggestions for students, policymakers, teachers and parents. Their suggestions also apply to working professionals.

Image credit: Business Insider

Consider the aim of the assignment or project

The researchers acknowledge that perhaps different mediums achieve different aims. For example, is the goal to find an answer to a specific question? Is it to browse the newspaper for the day’s headlines?

Depending on the aim, one should pick the medium that works best.

Consider the task

The researchers discovered that if students were asked to comprehend and remember the main gist of what they’re reading, then there is no major difference between reading from a text or screen.

On the other hand, if the assignment requires more engagement and deeper understanding of the text, then students should read it in print.

The researchers say that “teachers could make students aware that their ability to comprehend the assignment may be influenced by the medium they choose. This awareness could lessen the discrepancy we witnessed in students’ judgments of their performance vis-à-vis how they actually performed.”

Read Slower

Researchers found that a select group of students understood the text better when they moved from print to digital. That is because they read slower when the text was on the screen compared to when it was in a book.

Image credit: The Hechinger Report

That suggests that students can be taught to read texts slower online as opposed to just skimming through them.

The Younger Generation Could Lose Out

Singer and Alexander worry that, we could lose something important if print disappears completely.

They said, “in our academic lives, we have books and articles that we regularly return to. The dog-eared pages of these treasured readings contain lines of text etched with questions or reflections.

It’s difficult to imagine a similar level of engagement with a digital text. There should probably always be a place for print in students’ academic lives – no matter how technologically savvy they become.”

It perhaps should be something we should all be concerned about, especially in light of multiple studies that report distinctive differences between reading on paper and on-screen.

Before we look at those studies, let us better understand how our brain interprets text, or how it functions when we read. That way, we can better comprehend the literature on the differences between reading on paper versus digital interfaces.

How the Brain Interprets Written Text

Writing was invented (comparatively) recently in our evolutionary history – it is not inherent in us like talking is. Think about it this way: you could talk even before you could read.

And hearing words and learning their sounds is a crucial part of learning a language. However, before we can read, or read quickly, our brains must see words as well.

That is the finding of neuroscientist Maximilian Riesenhuber and his colleagues. The scientists imaged the brains of a group of college students before and after they learned a set of 150 nonsense words.

Image credit: Seeker

They found that before they learned the words, their brains registered them as a mishmash of symbols. However, as they were trained to give those words meaning, the words looked similar to words they used daily, like dog or apple.

They noticed that the brain saw the words instead of sounding them out. It was almost like an adult learning a foreign language based on a new alphabet system.

Students would have to learn the new alphabet, assign sounds to each symbol; and in order for them to read the words, they would have to sound out each letter to put words together.

In a person’s native tongue, instead of sounding out each letter, the brain conditions itself to recognize groups of letters it often sees together, like c-a-r, and assigns a set of neurons in a part of the brain that activates when the letters appear.

That's what Riesenhuber saw in the MRI images of the volunteers’ brains. The visual word form area, which is located in the left side of the visual cortex, is basically like a word dictionary. It houses the visual representation of the letters making up thousands of words.

It is the visual dictionary that makes it possible to read at a fast pace as opposed to sounding out each letter when we read. When the participants were taught to read the meaningless worlds, that part of the brain was activated.

The human brain, beyond treating individual letters as physical objects, can also perceive a text in its sum as a physical landscape.

What does that mean?

When we read, our mind constructs a representation of the text in which meaning is attributed to structure. The essence of those representations is not yet clear in science but is most similar to the mental maps we create of physical spaces, landscapes and terrain.

Several studies report that people often remember where a text appeared when they were trying to locate the text. For example, you might remember that you passed by a greenhouse before you started hiking up a hill. Just like that, you may remember Elizabeth’s embarrassment at her mother’s inability to comply with social conventions on certain pages of Pride and Prejudice.

Let’s look at studies that show why you should read more text on paper than on screen for work or leisure.

Recollecting Information: Paper versus Screen

A study found a difference in recollecting information when reading from paper versus on-screen. Interestingly, they found that when learning something, it is best to process information from different media forms.

If you want to remember dates of certain events, a screen may help you better remember them. But if you want to remember why or where an event happened, then paper would be the best choice.

Scrolling Disrupts Our Memory and Focus

A study on scrolling found that we don’t learn as much nor have a reference point as we do with books, when we scroll.

It found that we are more likely to remember which page and which part of the page a text comes from when we read from a book, but with online scrolling, the reference point is missing. Additionally, with scrolling, we don’t realize how many pages we have scrolled through and that can at times be daunting.

The researchers wrote, “when the text was presented in a more traditional pagelike format, readers were better able to relocate information than when the same information was presented in scrolling format.

In addition, presentation in discrete pages led to better memory for details contained within the text.”

Furthermore, the display brightness of a screen could interfere with reading experience and comprehension.

You may find that when you read for pleasure, or that if you are an academic, you prefer reading research on paper text. If it is on a screen, you may have less focus on the text or get tired from the brightness of the display.

Other studies have shown that in addition to screens being a burden on people’s attention more than paper, people do not use as much mental effort on screens in the first place. Some people subconsciously think reading on a computer is less serious than reading on paper.

A 2005 study also showed that people who read on screens take a lot of shortcuts. They spent more time browsing and scanning text than people who read on paper (who are more likely to read the text twice).

People also seem less likely to use metacognitive learning regulation (setting goals, rereading difficult sections and checking how much you have understood while reading) when reading on screens.

A 2011 study found that people taking multiple-choice exams about expository texts on either screens or paper performed equally as well when under a time pressure. However, when they managed their own study time, people who studied on paper scored 10 percent higher.

Researchers hypothesize that it is because students who used paper approached the exam more studiously than people who read on screens. They were also better able to effectively direct their attention and working memory.

Screens Interfere with Intuitive Navigation

When you read from a page in a paper book, you can focus on that page because you know where it is in relation to other parts of the book. You know where the book begins and ends and where that page is in relation to the entire book.

You can even feel the thickness of the pages, feeling what you read in one hand and what you have left to read in the other hand. Turning the pages of the book marks a footstep on a trail and you can determine the pace and distance you have traveled.

The pages also make a unique sound when turned and you can underline and highlight sentences with ink to permanently alter the paper’s chemistry. Digital texts are yet to replicate that tactility.

Indeed, most screens interfere with intuitive navigation of the text and prevent people from mapping out the journey in their heads.

So a reader of a digital text could appear to be scrolling through an endless stream of words, tapping forward from one page to the next or using the search functionality to find specific phrases.

They will also find it difficult to see a passage in the context of the entire text. Plus, an e-reader weighs the same regardless of whatever book you’re reading.

So e-readers cannot recreate certain tangible experiences of paper texts that some digital readers are nostalgic for. They also prevent people from enjoying long texts in an intuitive way. And those difficulties could hinder reading comprehension.

In particular, some researchers have found that those differences create haptic dissonance to deter people from using e-readers. Simply because people expect books to feel, look and smell a certain way. And when they do not, reading can become unpleasant.

In fact, a few studies have shown that screens can impair our ability to fully comprehend a text by limiting how we navigate texts.

A 2013 study found that students who read texts on computers performed worse that those who read on paper.

The researchers asked 72 10th graders with the same level of reading ability to study a narrative and an expository text. Half the students read the texts on paper and the other half read them on pdf files on computers with 15-inch LCD monitors.

The students then took reading comprehension tests with multiple-choice and short-answer questions. (They had access to the texts while answering the questions.)

The authors of the study think that students who read the pdf files on a computer found it more difficult to find specific information when referencing the texts. That is because they had to scroll or click through the pdfs section by section.

Students who read on paper were able to hold the entire text in their hands and quickly switch between different pages. Due to the ease of navigation, paper books and documents may better aid reading comprehension.

People also say that when they really want to understand a text, they read it on paper. In a 2011 survey, a majority of graduate students at National Taiwan University reported browsing a few paragraphs online before printing out the whole text for more thorough reading.

Reports also show that sensory experiences that are cognate with reading, especially tactile experiences, matter to people more than we think.

But for some people, the convenience of owning a slim and portable e-reader can remove any attachment they may have to paper books.

The Effects of Screens on “Knowing”

It is important to note the distinction between remembering something (when and how one learned it) and knowing something (knowing that something is true without remembering how one learned it).

It is a distinction that psychologists often make. In general, remembering is a less potent form of memory that is likely to blanch unless it is transformed into more secure long term memory that is known henceforth.

A 2003 study that asked 50 students to read study material from an economics course either on a computer or a booklet, found that students who read study material on a computer relied more on remembering than knowing.

Whereas, students who read study material on paper learned the study material more thoroughly versus quickly. They did not have to spend as much time parsing their minds for information from the text as they often knew the answers.

Wrapping Up

Although many studies have shown that people comprehend what they read on paper better than they do on screens, the difference is minimal.

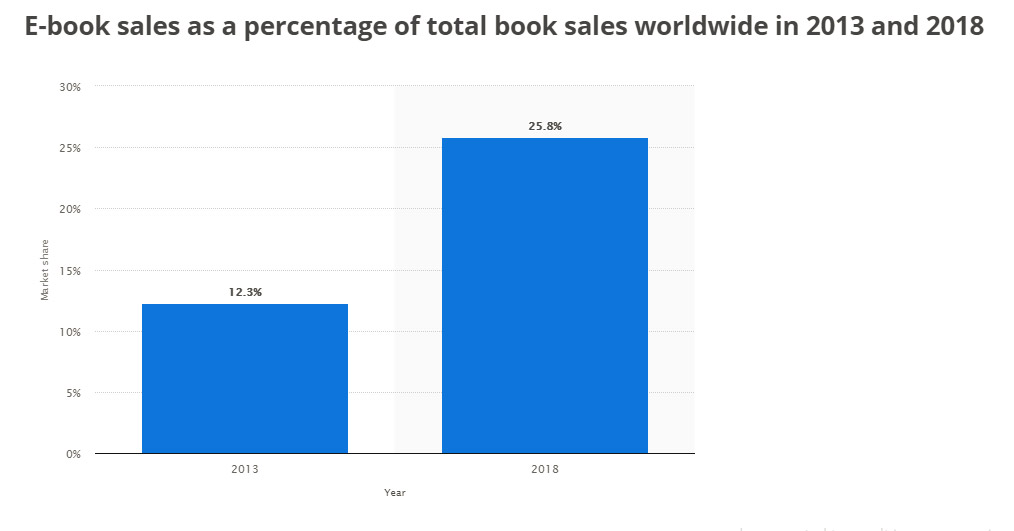

And it appears that most people still prefer paper text, the digital sales market share was just a little over 12 percent in 2013 but is expected to more than double this year.

Image credit: Statista

True, when reading long pieces of text, paper may still have an advantage. But text is not the only way to read and new ways to read will be added in the next decade. In fact, Kindle and Apple iBooks are trying to simulate paper reading as much as possible.

Perhaps digital books will follow the same trajectory as digital music? For example, people love curating and sharing digital music. So if e-readers and tablets have more sharing and social interaction capabilities than they currently do, the digital sales market could substantially increase.

The bottom line is, we read for pleasure and to learn. So pick the best mode that best works for you: digest and enjoy it.

Happy reading!